Some folks have been asking about my thoughts on recent writing. This is normally hazardous ground, because on one hand, it makes sense to want to promote the work of friends, but there is also the risk of falling too far into the “writing about writing” trap, and in the case of people you “know,” it can be difficult to say nasty things.

Luckily, I have no such compunction about tagging people in my complaints about their work. So let’s open up this new, wide, vista in exploratory Ecologica by half-conceding.

I’ll write about something new! But it will not be something by anyone who has requested a look-over. This one also has the advantage of saving me the need to complain, because we’re going to talk about Anna Krilopavola’s lighting fast story over at Soft Union from last week, “A Vomitorium in the House of Love.” It might actually be perfect.

I’d give you some background on Anna and her work but I don’t know much, can’t pronounce her name properly, and mostly just read her stories over and over trying to figure out why they are so mesmerizing. None of them target any of my brain receptors and I’m definitely not in the prime audience. She’s just really good with words and stories.

Anyway, she’s always spraying stories in various formats, but her collection Incurable Graphomania1 which is published by Apocalypse Confidential, the very same folks who ran some of my poetry last month, and is right here. Ah yes that’s how I’m being technically unethical. Instead of telling you to go buy it, I’m gonna tell you to go read it.

Now this story, the one we are worried about today, this thing is only 1036 words, so go read it right now, and listen to this song we are also gonna talk about while you do. They should finish up right around the same time and we will all be on an even playing field.

I am sure some of you didn’t do as requested though, so here’s the logline:

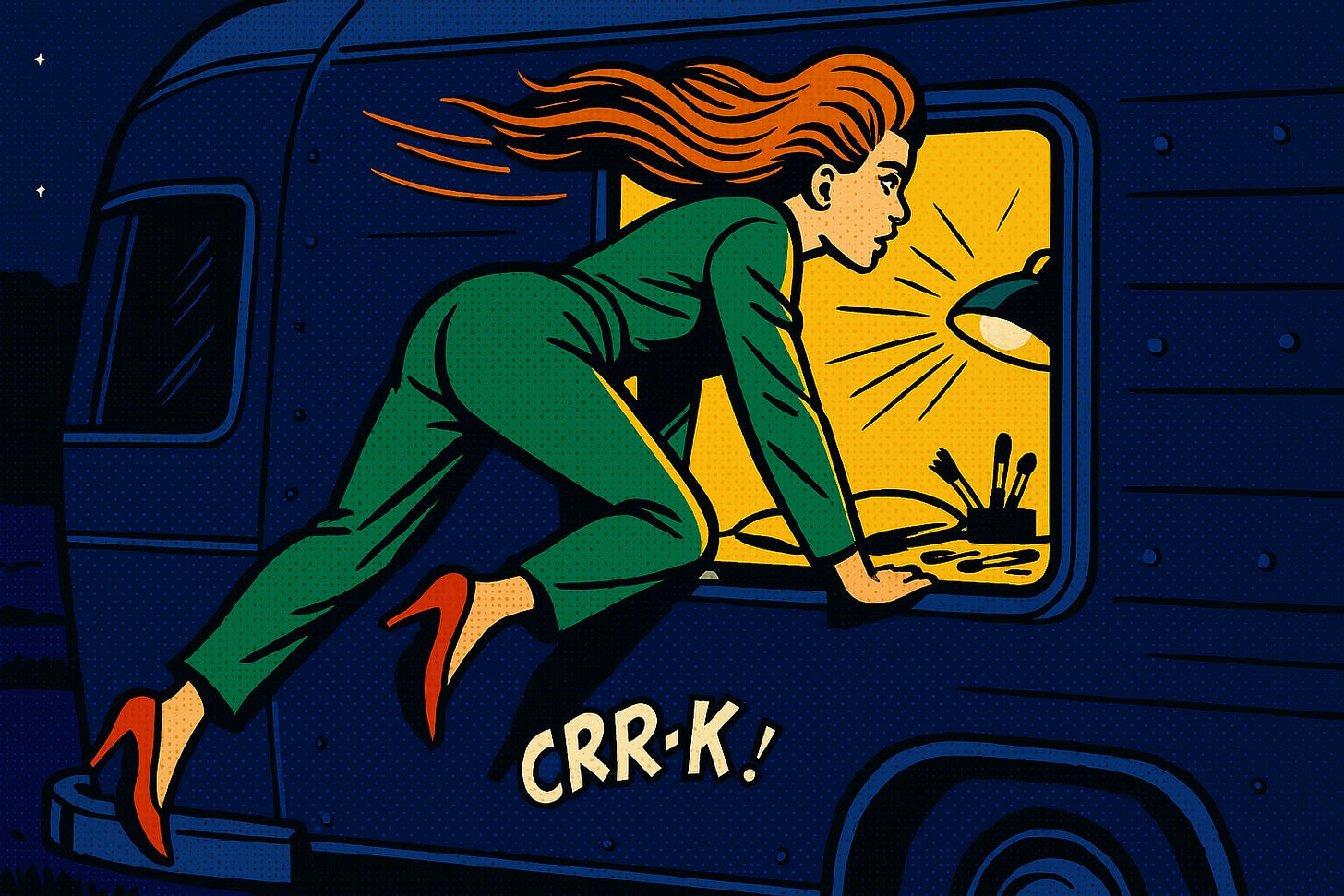

Julien, a newly-thin actor obsessed with his makeup artist Electra, spirals into a public, self-destructive eating binge after witnessing her with the film’s obese director, only for Electra to crawl through his trailer window, clean him up, and reunite with him in a scene of mutual physical surrender and messy, humiliating intimacy.

What makes “A Vomitorium in the House of Love” more than just a sharp little farce about heartbreak is how it sidesteps the accustomed “alt lit” circuits of confession and emotional exposition in favor of pure action. We get to laugh along with bodies moving, humiliations accruing, appetites exposed. The story works not as an allegory or a personal essay but as a precise economy of dignity and self-destruction: every calorie is a wager, every physical gesture replaces what another writer would put in a monologue. I want to look at how Krilopavola constructs this world almost entirely through physical dependency, transactional dignity, and how she uses the internet as a simple accelerant rather than a force of alienation. Most of all, I want to see what happens when romance is allowed to shed every scrap of dignity, becoming not a mutual understanding, but a public, physical mess.

Then I’m going to stick the story in a room with Bob Dylan and see what happens.

The overwhelming fact about “Vomitorium” is that it is constructed entirely out of gesture, and physiological process rather than the self-conscious, emotionally-masticated interiority of the autofictional “I.” The story itself signals, “reaction, not recognition.”

Consider how Krilopavola introduces us to Julien’s dependency:

“Electra tapped her brush against her left wrist before using a small piece of plastic to shield Julien’s eyelashes from her matte powder. Sometimes it got into his eyelashes and made his face look wide and washed out.”

Already, agency is displaced from confession to process. Julien’s vulnerability is bodily: he is being worked on, adjusted, rendered, and protected by Electra’s “small piece of plastic,” not by any spoken reassurance. His “wide and washed out” face, threatened by accidental powder, is less a self than a field of contingent surface effects. More Laurel & Hardy than the stuff of Proustian reminiscence, and that is good.

The eroticism, too, is a function of proximity and deprivation. Crucially, poor Julien doesn’t even really have a say in it:

“Julien had fallen in love with Electra after being forced to sit in her pheromones with his eyes closed, barely breathing as to not blow the powders around, oxygen deprived, crazy for her.”

No monologue, no slow-burn “getting to know you,” no text chain of declarations: “after being forced to sit in her pheromones… barely breathing.” The grammar of desire is saturation, inhalation, denial-of-breath. The line’s paradox is unmistakable: love is born in forced stillness, in a kind of synesthetic asphyxia. He is not allowed to see her, not allowed to speak—only to absorb and react.

When Julien tries to recover some dignity, asking, “Could we do a little less blush today, Electra? I look like a damn travesty,” Electra doesn’t respond with emotional reassurance or banter. Instead: “Electra didn’t know what that word meant.”

Now, in addition to just being funny, this bit hammers on the narrative’s point: her bodily self-possession: “a condescending grin that cracked her patchy lipstick,” “adjusted her apron,” “refastened the apron strings.” Electra’s reply is not verbal, but physical: she reasserts her authority through gesture, tool, and touch.

This is the organic unity of the story: what would be “talked through” in another writer’s hands is “worked through” here by means of action, manipulation, and the relentless materiality of bodies. The body is not a metaphor, it is the site and the substance of all drama!

“Vomitorium” additionally, crucially, constructs an economy of dignity through a spectacular and bitter irony. For Julien, dignity is a matter of renunciation and self-denial:

“He had worked hard all year to lose thirty-six pounds and look like less of a ruddy alcoholic for his gladiator role.”

This is capital in its purest physical form. Thirty-six pounds is the residue of “a year of self-denial,” becomes both a career wager and a currency for desire. Yet the story’s central irony is that the body, while mortgaged to career and love, is also grotesquely devalued and inverted by those very structures.

The counterpoint to Julien’s sacrificial discipline is Orpheus Peet, the director:

“After he started working behind the camera, he started to balloon, and the bigger he got, the longer his films became. Every fifty pounds he gained added half an hour to his runtime. His latest was predicted to pass the four-hour mark.”

It’s another perfect, self-contained irony: Peet’s weight is not a liability but a source of authority and creative excess. His films, and his body, both become more massive and ungovernable, where Julien’s lost pounds earn him only “less of a ruddy alcoholic” look (and, by implication, possibily less dignity, as he’s humiliated and ultimately cuckolded but not to get too far ahead…). Peet’s indulgence is rewarded by artistic sprawl and gravitas. Julien pursues a dignity the world of the story, and of its film-within-a-story, will not honor.

This irony is not just social; it is structural. The story’s internal economy, to quote Cleanth Brooks, is “a pattern of resolved stresses”: every instance of earned virtue is systematically undercut by a grotesque inversion, a comic/sad “reward” inverting any expectation of moral cause and effect.

That refusal established the grounds for the story’s volte, or catastrophe. “He [Julien] lost his mind when on the twelfth day of filming, he came to his makeup chair early just to find it straining under the weight of Orpheus, who Electra was struggling to mount like an assisted dip machine.”

“Straining under the weight.” The phrase is literal and symbolic, as is “struggling to mount like an assisted dip machine.” Electra’s physical intimacy with Peet is not just a sexual act but a grotesque tableau of effort, leverage, and mechanical comedy. The phrase “assisted dip machine” mocks both the gym culture that produced Julien’s “impressive calves” and the very concept of grace or agency in love.

Julien’s response is immediate and bodily, not mediated by introspection:

“Julien stopped going to the gym the next day. He gave crafty three thousand dollars in cash to bring him all the cheese and fruit platters they could carry. He procured six bottles of wine and demanded the bag of shake he found in a teamster’s cup holder.”

Again, no speech, no soliloquy, no “what does it mean”: action, consumption, surrender. His solution is not to win Electra back, but to become Orpheus—to mimic, through eating, the body that has “won.” The absurdity is made total when he turns this act into a performance for the public:

“He stacked the trays on his bed, opened a bottle of wine and his laptop, and turned the webcam onto himself.

There is a mad, paradoxical logic at work: To regain love, one must annihilate the body one sacrificed for status; to become attractive, one must become grotesque. Here, Krilopavola shows us not just irrational male desire but its mimetic, performative collapse. If I have one complaint with the story’s realism, here, its that this should not have worked. But we are not in my world.

“Vomitorium”’s climax is neither reconciliation nor mutual confession, really, but an objective spectacle of mutual abasement and animal comfort— what Yeats might have called “the fury and mire of human veins,” on one of his better days. The entry point is not the heart, but the window of a trailer, a literal passage for bodies, appetites, and everything unspoken:

“She hoisted her body through the window and fell onto Julien’s cot… She took a makeup wipe out of her apron to clean the vomit off his cheek… They drank wine from the bottle, ate brie by the handful…”

Notice how the sequence of events is stripped of the customary signals of romantic resolution? There is no apology, no accounting of feelings, no verbal attempt at catharsis. Instead, there is only the raw, unmediated presence of bodies and their hungers. Electra’s entrance is clumsy and feral; her gesture is immediately practical and intimate as she cleans the vomit off his cheek. The reunion is consummated not with words but with shared animal excess: wine drunk from the bottle, cheese eaten by the handful, oily hands wiped on the bedspread. The abject details…the lingering vomit, the carelessly discarded apron and spilled brushes…are not narrative obstacles to be overcome, but rather the conditions of union.

The story, the morsel, refuses the standard trajectory of reconciliation as mutual understanding. Instead, Krilopavola insists that love, if it happens at all, is achieved only through the total collapse of propriety, in the aftermath of ruin and exposure. The window ceases to be a symbol of communication or transparency and becomes simply a hatch through which appetites crawl and are met. Even the last line, Julien’s mock-threatening promise, “By the time I’m done with you, you won’t be able to fit through that window,” lands as a kind of anti-redemption. What is offered is not restoration, but a grotesque solidarity: love as shared excess, mutual undoing, animal ecstasy in the ruins of self-control.

That’s how you’re actually supposed to do irony. Beautiful.

To tack on a final technical note, it’s also refreshing here to see the internet itself sidelined, despite being a story about people who are obviously online natives, and story that is read online.

The internet’s role in “Vomitorium” is not to alienate but to accelerate, serving as both stage and time-compressor: The webcam is not the story’s center but an accelerant, compressing humiliation, appetite, and breakdown into instant spectacle: Julien again, doesn’t confess, he acts, devouring food on camera as the crisis plays out for an audience. This mirrors the structure of the flash short story itself, which, like the internet, collapses duration and forces (we would like to think!) swift, embodied resolution; what might have unfolded slowly in another form is instead rendered with ruthless immediacy, crisis and exposure arriving all at once for both character and reader.

Now since this is me, and I’ve already moved into the sunlit uplands of total simpage, I’m going to strain our relationship even more by comparing this woman’s story to a Bob Dylan song, and not just any Bob Dylan song either, but one that recently made my top ten list, and from which I stole no fewer than six lines for my poembook, “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?”

Yea, she made it easy this time.

The premise: a woman is trapped in a room with a man who invents and broods and manipulates, while Dylan, the voice from outside, urges her to just move; crawl out the window, don’t wait for permission or understanding, don’t worry about dignity or consequences. The refrain is both a taunt and a dare:

“Hey, crawl out your window

Come on, don’t say it will ruin you.”

What matters is not an emotional declaration, but the leap, the act, the rupture with passivity. The window is not a place for confession; it is the only exit from stasis, the portal from paralysis to life.

In Dylan’s lyric, the room is a kind of tomb, stifling, maintained by a man who “sits in your room, his tomb, with a fist full of tacks / preoccupied with his vengeance.” The world on the other side of the window is uncertain, but the only real risk is in staying, in continuing to “test his inventions,” to become “frightened of the box you keep him in.”

“Come on, out your window

Come on, don’t say it will ruin you

You can go back to him any time you want to.”

Read against “Vomitorium,” the logic is reversed but the energy is the same. Where Dylan’s speaker urges an escape from paralysis, Krilopavola’s story stages salvation as invasion. The boundaries are still shattered, and what matters is not what is said or explained, but the “movement against paralysis.” Dylan’s plea: “don’t say it will ruin you”—lands like prophecy: the price of escape or entry is always ruin, but ruin is the only place where something new can begin.

Had enough yet?

Hilariously, I was introduced to this work by someone who thought it might be relevant to my work on “Knowledge Graphs” (AI adjacent). Nope, not at all, and “graphomania” refers, rather, to the compulsion to write. A lot going on there.